Brief History

Western art has integrated representations of plants, flowers, and trees since its earliest times, employing them in diverse iconographic contexts. If we trace the origins of botanical symbolism, we inevitably arrive at Ancient literature, where the famous story of Narcissus, the vain youth who fell in love with his own reflection and, according to tradition, was transformed into a flower bearing his name, exemplifies the way in which plants were used as moralizing metaphors.

Much of the information regarding beliefs and traditions connected to plants has come down to us through also from one of the most important encyclopedists of Antiquity, Pliny the Elder. His monumental Naturalis Historia (comprising 37 volumes that cover nearly all domains of ancient knowledge) includes a substantial section devoted to botany. This work played a fundamental role in transmitting and shaping later interpretations of ancient conceptions of the natural world.

Approximately fourteen centuries later, in the Renaissance, with the rediscovery of Antiquity by scholars and artists, we witness a revival of classical texts and, implicitly, of floral symbolism, frequently employed in religious compositions. Among the most commissioned subjects of the 14th-15th centuries is the Annunziata, depicting the moment when the Archangel Gabriel announces to the Virgin Mary that she bears in her womb Jesus, the Son of God. An analysis of the paintings on this theme in the Uffizi Gallery reveals the constant presence of lilies, a symbol with a precise role, meant to evoke Mary's chastity and purity.

Sandro Botticelli, Annunciation, 1489-90, The Galleria Uffizi Collection

In Northern Renaissance art, carnations appear regularly, regarded as emblems of earthly love and marriage. This association is evident in wedding and betrothal portraits, where the bride is often depicted holding a flower related to the carnation.

Rembrandt, Woman with a Pink, early 1600 (The Met Collection)

With the emergence of Impressionism and the Modern Era, the boundaries of the visual arts were freed from academic constraints, giving way to an unprecedented creative momentum. Flowers and plants were no longer merely symbols with religious or allegorical roles, nor simple still-life representations; they became opportunities for chromatic and sensory experimentation. Monet, Renoir, Matisse, and Van Gogh are just a few of the names that transformed the floral subject into a field for exploring light, color, perception, and emotional states, marking a profound shift in the way nature was reflected in art.

Henri Mattisse: The Cut-Outs, Tate Modern, 2014 (Installation view)

With such a vast repertoire and a solid historical tradition, it is unsurprising that flowers continue to represent a focal point of interest for both modern and contemporary artists. In this essay we turn to three of them: Georgia O'Keeffe, Constantin Flondor, and David Hockney.

Georgia O’Keeffe

"I had to create an equivalent for what I felt about what I was looking at – not copy it.", Georgia O’Keeffe

We cannot speak about representations of the natural world in the history of modern art without referring to the work of Georgia O’Keeffe (1887–1986). Over the course of a long career, her primary subjects were landscapes, flowers, and bones, explored in series over many years or even decades. These images always derived from her life experience and were directly or indirectly connected to the places where she lived, from the landscapes of New Mexico to the gardens and flowers observed with an almost scientific attention.

Her flowers, often depicted on a monumental scale and with details bordering on abstraction, have been interpreted by critics in multiple ways. As early as 1919, Alfred Stieglitz, the photographer who promoted O’Keeffe’s work and later became her husband, advanced a Freudian reading, suggesting that her flower paintings were direct analogies of the female sexual organ. This interpretation was revived in the 1970s by feminists, who saw in her work a manifesto of female empowerment. Yet O’Keeffe herself consistently rejected this reductive reading, insisting that her intention was not to copy nature but to create a visual equivalent of her own experience and emotions in relation to what she observed.

Georgia O'keeffe, The white Calico Flower, 1931, The Whitney Museum of American Art Collection

Georgia O'keeffe, The white Calico Flower, 1931, The Whitney Museum of American Art Collection

On the occasion of the major Tate Modern retrospective, curator Tanya Barson emphasized the importance of moving beyond the clichéd interpretation that, for nearly a century, had reduced O’Keeffe’s work to a single key of reading. Today we are witnessing a restitution of the complexity of her oeuvre through “multiple readings,” reaffirming the profound dimension of her exploration of the relationship between nature, body, and spirit.

Constantin Flondor

“Nature is constantly teaching me lessons. It is the supreme pedagogue I have,”, Constantin Flondor for Propagarta

For Constantin Flondor (b. 1936), founding member of the groups 1+1+1 (1966–1969), Sigma (1969–1981), and Prolog (since 1985), nature has always been a partner and guide. Displaying an early interest in the study of primordial elements—air and earth—the artist recalls in an interview how, throughout his career, he always needed a point of reference, whether drawn from the geometric universe and mathematical algorithms or from the models provided by nature itself.

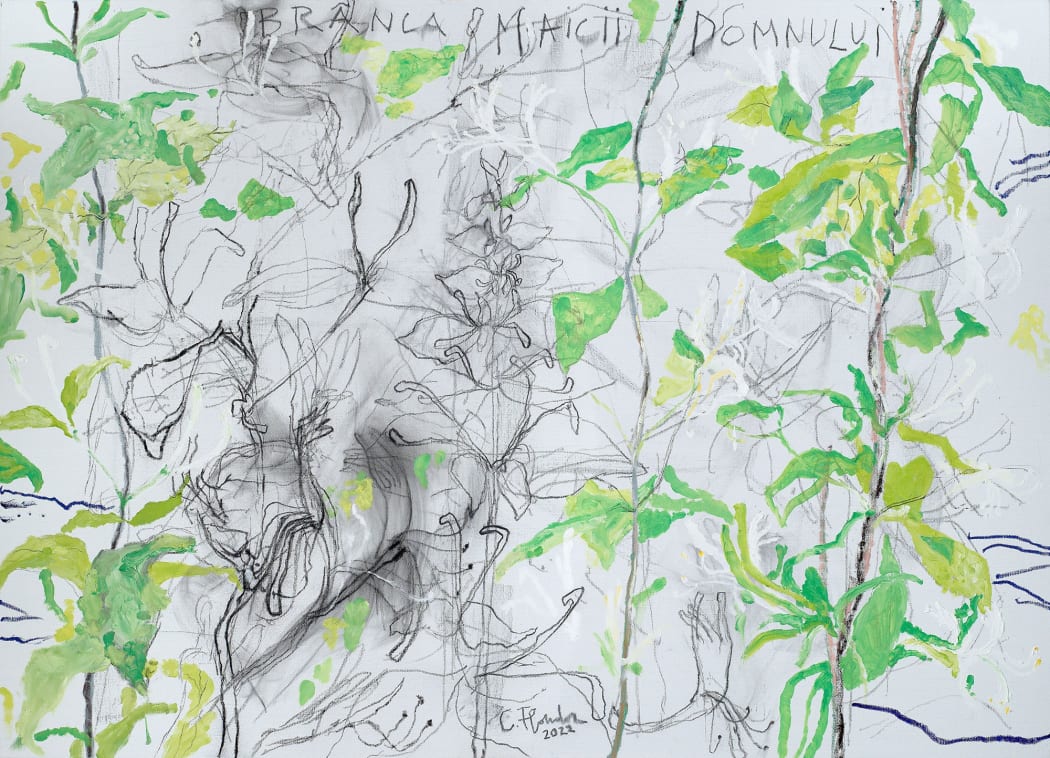

With a pedagogy deeply rooted in his teaching experience, Flondor developed his own approach to perceiving the environment: he observes with the attention of a biologist, analyzes, encodes visually, and only afterwards translates everything onto paper. “Visual information must be simplified,” he states, and this conception is clearly reflected in his works. Flondor’s flowers are not descriptive renderings but essentialized forms, dissolved into an almost abstract language, where floral structures become rhythmic games between emptiness and fullness, presence and absence.

For Flondor, the sunflower, the elderflower, clouds, or a snowflake become symbols of fragility and transience, a consciousness of the ephemeral mirrored in the elegance of his vegetal brushstrokes. Not by chance, the current exhibition “The Kingdom of the Garden” in Viscri revisits precisely this theme, bringing to the forefront the artist’s reflection on the fragility of nature and the ephemerality of existence.

Constantin Flondor at Viscri, before the opening of his exhibition "Garden Empire

Constantin Flondor at the opening of his latest exhibition at Viscri, "Garden Empire"

Constantin Flondor at the opening of his latest exhibition at Viscri, "Garden Empire"

1) Constantin Flondor, Untitled, 2022; 2) Constantin Flondor, Untitled, 2022

David Hockney

“Whatever the medium is, you have to respond to it. I have always enjoyed swapping mediums about. I usually follow it, don’t go against it. I like using different techniques”, David Hockney

If in Flondor’s case nature is approached through spiritual reflection and the essentialization of forms, Hockney’s perspective is radically different, oriented instead toward new visual technologies. His fascination with flowers dates back to the 1960s, yet beginning in the 2000s the artist turned to studying flowers on the iPad, exploring the potential of digital drawing and expanding the conventional limits of painting.

The exhibition organized in 2023 at Pace Gallery, 20 Flowers and Some Bigger, is a telling example of how experimentation with new media has become organically integrated into Hockney’s artistic practice. Inspired by daily life during the pandemic, which he spent at his 17th-century house in Normandy, the artist produced an extensive series of digital works with flowers as their central subject. Grounded in his daily observations, Hockney embraced the iPad, a medium of unique immediacy, which allowed him to be extremely prolific in representing his home, the changing seasons, and the surrounding countryside.

In his now-famous dialogue with Hans Ulrich Obrist, published in 2015, Hockney emphasized that we are at the dawn of a new visual era, defined by the continuous reinvention of the image. This observation may be interpreted as a key to understanding his artistic intentions and as an essential indication of the directions he would explore in the years that followed.

Sources

- https://www.metmuseum.org/essays/botanical-imagery-in-european-painting

- https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-van-gogh-okeeffe-art-historys-famous-flowers

- Constantin Flondor, When eye touches cloud, ed. Alina Serban, Vellant, 2021

- https://propagarta.ro/interviuri-acasa-la-in-atelier-la/de-vorba-cu-constantin-flondor-despre-expozitia-imparatia-gradinii-natura-imi-da-tot-timpul-lectii-ea-este-pedagogul-suprem-pe-care-il-am/

- https://putereaacincea.ro/pictorul-constantin-flondor-imi-place-sa-privesc-cu-luare-aminte-detaliile-acestei-lumi/

- https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2022/10/04/david-hockney-floral-ipad-paintings-five-galleries

- https://www.pacegallery.com/exhibitions/david-hockney-20-flowers-and-some-bigger-pictures/

- Hans Ulrich Obrist, Lives of the Artists, Lives of the Arhitects, p.1-p.53, Penguin, 2016

- https://www.okeeffemuseum.org/about-georgia-okeeffe/

- https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2016/mar/01/georgia-okeeffe-show-at-tate-modern-to-challenge-outdated-views-of-artist

- https://www.metmuseum.org/essays/georgia-okeeffe-1887-1986

- Celia Weisman, O'Keeffe's Art: Sacred Symbols and Spiritual Quest